A while ago I penned a 5,000-word piece for The Nightwatchman about the legendary Australian cordon of Ian Healy, Mark Taylor, Mark Waugh, Shane Warne and Steve Waugh, all of whom would go on to play 100 Tests in the baggy green. The editor (who tampered a little too forcefully with jokes she clearly didn't get) called it 'A Cordon of Porcupines' (I blogged about it a couple of years ago).

Anyway, the good folk at Wisden reproduced the opening salvo of said piece recently for their own blog. It can be read here, if you fancy a squizz:

'A Cordon of Porcupines' Intro

Showing posts with label writing. Show all posts

Showing posts with label writing. Show all posts

Wednesday, 19 August 2015

Wednesday, 29 April 2015

BAJAN MEMORIES

My second regular Cordon blog for ESPNcricinfo was as much about what I left out as what went in. What goes on tour stays on tour, they say. Perhaps.

Either way, publication of this piece has put me back in touch with three of the 16-strong touring party, and in the thread below several dusty and long-forgotten memories were pulled from the attic: (1) a player who managed to defecate while unconscious, stinking out the whole condominium, although not enough to rouse one of his roommates; (2) getting hustled when buying the ingredients for jazz cigarettes, the first batch we were sold being kosher, the second, from the same guy, later seen with a machete tucked into his basketball socks, probably better served to improve a pasta sauce; (3) a player buying the ingredients to cook a spaghetti bolognese in order to win the heart of an ebony princess plucked from the dancefloor of a nightclub; (4) said player not quite making it to the end of an intimate encounter before having to run through the streets of Bridgetown to catch a minibus back to the condos to pick up luggage and head to the airport; (5) a player downing a jar of local hot peper sauce, claiming it was "muppet" and "Haagen-Dasz"; (6) the many, many vodka-pineapples and rum punches drunk on the refined cultural experience that was the Jolly Roger cruise ship; (7) an inebriated player standing on the foot-rest of a bar stool and toppling Del-Boy-like flat on his face; (8) meeting ex-Windies and Essex all-rounder, the late Keith Boyce, and hearing him predict the decline of the then still dominant team; (9) getting into the local vibe by playing saucepans at the West Indies versus Australia Test match, the first session of which John Woodcock of The Times said was the best he'd seen in 60 years of watching cricket; (10) the tour anthem, the ubiquitous 'Hot Stepper' by Ini Kamozi.

Ah, good times. I'll never return as a youngster, but I will return for cricket one day. What goes on tour gets recycled as a blog about a blog, right?

Once upon a Caribbean Cricket Holiday

Thursday, 12 March 2015

SAQLAIN MUSHTAQ: GLEANINGS

Another Gleanings interview, this time with the founder of the doosra: Saqi bhai.

Parts of our conversation that didn't make it included a few thoughts on his brief time sub-pro'ing for Burslem in the NSSCL, and his comments on Imran Tahir (which were positive).

We didn't speak about the time a certain former housemate of mine and one-time colleague at Wollaton CC lofted him for a straight six to bring up his maiden Premier League hundred. He wouldn't be drawn on whom, out of him, Usman Afzaal and Alex Tudor, wasn't being paid the year he played for West Indian Cavaliers (league rules limiting the number of paid players to two).

And he claimed not to know anything about the nightclub that Saeed Anwar – the man responsible for the increasing religious devotion in the Pakistani squad during the 1990s – used to have in the basement of his Lahore residence, before the tragic death of his three-year-old daughter led him to seek solace in Islam.

Still, he told me a couple of funny yarns about his cricketing days, and one heartbreaking story of a talented quick bowler who injury got the better of.

Saqlain Mushtaq: Gleanings

Tuesday, 17 February 2015

MY FAVOURITE CRICKETER: JACK RUSSELL

OK, so he isn't really my favourite cricketer, but Brian Lara had already been taken...

Anyway, it was a great honour to have a piece accepted for this cricinfo column, which has featured many of my favourite cricket writers (perhaps there's a column in that?), including: Gideon Haigh (on Chris Tavare), Rob Smyth (on Martin McCague), John Hotten (on Geoff Boycott), Rob Steen (on Flintoff), Jarrod Kimber (on Bryce McGain), Malcolm Knox (on Allan Border), Alan Tyers (on Botham).

It's well worth checking a few of these out. There are several other good ones: Lawrence Booth on Allan Lamb, Tanya Aldred on Shane Warne, David Frith on Ray Lindwall, Peter Roebuck on Harold Larwood, Andrew Miller on Gus Fraser...

Meanwhile, here's my text, but without the mangled edit on one of the sentences (this in itself might provide a clue as to why Kack was my [second] favourite cricketer). Appropriately, it's also perhaps my favourite piece for ESPNcricinfo thus far. The original (which I called Bristles in Bristol, so the editor redeemed himself somewhat) can be found here.

* * *

TOP DOG OF THE UNDERDOGS

Growing up in a minor county, my first in-the-flesh exposure to famous cricketers usually came in those sorely missed David-and-Goliath games of the old NatWest Trophy. Malcolm Marshall, Ezra Moseley, Allan Lamb, Robin Smith and Aravinda de Silva all came to play Staffordshire at Stone, my home town. And before them, in 1984, when I was 11, was Jack Russell, then an unknown member of an unglamorous Gloucestershire side who arrived to dot the i’s and cross the t’s of an inevitable victory.

I’d love to claim it was love at first sight, but the truth is I barely noticed him – which, conventional wisdom will (erroneously) tell you, is the hallmark of a good wicketkeeper. However, I do remember when the seduction process was complete, and it took a single ball to seal it. It was the moment the pleasantly attractive girl from your physics class turns up to the school disco in pink hotpants.

To this day, I’ve only seen one legside stumping off a quick bowler in Test cricket, probably fewer than the number of switch-hit sixes if I cared to think about it. Gladstone Small was the bowler, Dean Jones the man overbalancing at the crease, and Jack, with ninja-like celerity, hopping sideways while seeming stillness itself, the magician who whisked off the bails before gambolling like a lamb into the arms of Alec Stewart, later the quietus to his international career. Its unadulterated brilliance could be gauged from the reaction of the grizzled old pros converging upon him to celebrate: Ned Larkins, Eddie Hemmings, David Gower, Graham Gooch, all laughing at the absurd majesty of it all, a heist carried out to perfection. And that’s what a legside stumping feels like: pickpocketing the opposition.

My dad was a wicketkeeper. I wasn’t, although, strangely,

I often seemed to find myself walking out in pads and gloves to do it. It was

one long trauma. On one occasion, I lost a tooth; on many, I lost the plot. I endured

a West Indian

Test bowler pounding the ball into hotspots, broke several fingers (hands

groping round the batsman’s backside for a lost flight path), missed three stumpings

in a final off a leg-spinner who forgot the googly signal, and, worst of all, dropped three catches in a

single over off one of Jack Russell’s future teammates, Jeremy Snape, while

playing for Staffordshire Under-13s.

I’ve always thought wicketkeeping – specifically, standing up to seamers – the most difficult of cricket’s arts, with the possible exception of legspin, and so felt an exaggerated admiration for anyone who did it well. Jack’s silken glovework was, evidently, a marvel – the preternatural ease with which he took the awkwardly bouncing ball as it melted gratefully into those black mitts, body contorting yet hands smooth and slow, like an expert cocktail waiter sweeping through a busy room.

Neat and tidy as a keeper he may have been, but there was a meticulous scruffiness about everything else. The first year he sewed the three lions over the Gloucestershire badge on that trademark bucket hat was 1988, the second Summer of Love. He fidgeted his way to 94 on debut at Lord’s, each run an affront to the game’s aesthetics, and in the Ashes the following year made a maiden hundred in the city then known as Madchester. Little did my baggy-loving mates realize that my headgear was an homage not to the Stone Roses, but to a certain stumper from Stroud.

Jack’s batting was not a thing of beauty. In fact, crouching over his bat as he shovelled, swept, sliced and slapped, it was almost deliberately ugly, a calculated provocation, as was so much of his cricket. Even his leave-alone was in-your-face, pulling back the curtain rail then, like some feral neighbourhood kid, staring straight into your living room to see what he could nick. Or not nick, as was famously the case in his epic rearguard with Mike Atherton in Johannesburg, which he later immortalised in a painting entitled The Great Escape, aptly for such a staunch flag-waver. Ordinarily, I’d have been turned off by such obstinate quirkiness and untempered patriotism (even his keeping technique resisted the Australian fashion, as he saw it, for taking the ball on the inside hip), but his glovework redeemed all.

Jack was the eccentric’s eccentric in a métier given to eccentrics. Insisting your Weetabix are soaked for precisely eight minutes; having the same meal 29 nights consecutively on tour; taking a suitcase full of baked beans away because you didn’t trust hotel food; washing your own kit in the hotel room because you didn’t trust the staff – none of this suggests a man comfortable with flux and uncertainty. Yet uncertainty is what hung over much of his England career, whenever the runs dried up.

I’ve always thought wicketkeeping – specifically, standing up to seamers – the most difficult of cricket’s arts, with the possible exception of legspin, and so felt an exaggerated admiration for anyone who did it well. Jack’s silken glovework was, evidently, a marvel – the preternatural ease with which he took the awkwardly bouncing ball as it melted gratefully into those black mitts, body contorting yet hands smooth and slow, like an expert cocktail waiter sweeping through a busy room.

Neat and tidy as a keeper he may have been, but there was a meticulous scruffiness about everything else. The first year he sewed the three lions over the Gloucestershire badge on that trademark bucket hat was 1988, the second Summer of Love. He fidgeted his way to 94 on debut at Lord’s, each run an affront to the game’s aesthetics, and in the Ashes the following year made a maiden hundred in the city then known as Madchester. Little did my baggy-loving mates realize that my headgear was an homage not to the Stone Roses, but to a certain stumper from Stroud.

Jack’s batting was not a thing of beauty. In fact, crouching over his bat as he shovelled, swept, sliced and slapped, it was almost deliberately ugly, a calculated provocation, as was so much of his cricket. Even his leave-alone was in-your-face, pulling back the curtain rail then, like some feral neighbourhood kid, staring straight into your living room to see what he could nick. Or not nick, as was famously the case in his epic rearguard with Mike Atherton in Johannesburg, which he later immortalised in a painting entitled The Great Escape, aptly for such a staunch flag-waver. Ordinarily, I’d have been turned off by such obstinate quirkiness and untempered patriotism (even his keeping technique resisted the Australian fashion, as he saw it, for taking the ball on the inside hip), but his glovework redeemed all.

Jack was the eccentric’s eccentric in a métier given to eccentrics. Insisting your Weetabix are soaked for precisely eight minutes; having the same meal 29 nights consecutively on tour; taking a suitcase full of baked beans away because you didn’t trust hotel food; washing your own kit in the hotel room because you didn’t trust the staff – none of this suggests a man comfortable with flux and uncertainty. Yet uncertainty is what hung over much of his England career, whenever the runs dried up.

As the insecurities grew, ever more quirks and tics

were introduced. He began standing at forty-five degrees (and too deep, they

said), facing cover-point. The consistency dropped, as were one or two

straightforward catches, once prompting him to lock himself in his room for two

days. There was evident frailty there – a brain scan would doubtless have revealed

synapses held together with rubber bands and string – and sympathy duly morphed

into empathy.

By the time the decade – and his England career – was done, Adam Gilchrist had transformed perceptions of the keeper’s role forever. In Test cricket’s futures market, legside stumping stock had been ditched for batting pugnacity. Russell was part of a dying breed. Perhaps, with a frontline bowler who could have batted at No7, he’d have won many more Test caps than the 54 he accrued (and never wore). Instead, Stewart donned the gloves in an attempt to balance the side.

Yet the unmistakeable hue of genius never waned, and it was at Gloucestershire, in his final years, before chronic back trouble curtailed his career, that his regal brilliance truly flourished. John Bracewell, his coach, believed that it was only when he stopped thinking about being selected for England that he became “unquestionably the best keeper in the world”. Prior to this, he felt, Jack had been too conservative, too keen not to make mistakes, too keen to go unnoticed – thus giving the lie to the old saw. Now, with the coming of autumn, he stepped forward, right up to the stumps, and gave full rein to his gifts, the ringmaster in an unheralded Gloucestershire team that won six limited-overs trophies in three seasons.

On pitches the colour of gruel, Ian Harvey, Mike Smith et al created the anxiety, the asphyxiation, and as the veins popped in batters’ heads there was Jack the mosquito, puncturing their flesh for a slurp of claret. Barking – oh, he was barking – relentlessly at his teammates, he would habitually walk in front of the stumps to applaud and chivvy, all a pretext for irritating the batsman, getting in his space. It brought new meaning to occupation of the crease – here, in the sense of an invading army. The pickpocket had become a mobster. A bailiff.

I admired his brazen, cartoonish villainy. Face inscrutable behind those sunglasses, that daft hat and his bristles, Jack would narrate the batsman’s anxieties for the benefit of his swarming team. He gave this reluctant and increasingly part-time wicketkeeper something to aspire toward. Sure, my Teflon glovework would always be found wanting, but I could always usefully piss the batsman off.

It was not genteel comportment, but then the cricket I played wasn’t genteel. The existential stakes were high: glory, ignominy and self-esteem, all were forged by this innings, that shot, a catch, a victory. There was no place to be genteel. My nickname then was Dog (as in Scotty…), and the cricket was dog-eat-dog. And in that there was no better example, no more terrorising terrier, than Jack Russell, top dog of the underdogs.

By the time the decade – and his England career – was done, Adam Gilchrist had transformed perceptions of the keeper’s role forever. In Test cricket’s futures market, legside stumping stock had been ditched for batting pugnacity. Russell was part of a dying breed. Perhaps, with a frontline bowler who could have batted at No7, he’d have won many more Test caps than the 54 he accrued (and never wore). Instead, Stewart donned the gloves in an attempt to balance the side.

Yet the unmistakeable hue of genius never waned, and it was at Gloucestershire, in his final years, before chronic back trouble curtailed his career, that his regal brilliance truly flourished. John Bracewell, his coach, believed that it was only when he stopped thinking about being selected for England that he became “unquestionably the best keeper in the world”. Prior to this, he felt, Jack had been too conservative, too keen not to make mistakes, too keen to go unnoticed – thus giving the lie to the old saw. Now, with the coming of autumn, he stepped forward, right up to the stumps, and gave full rein to his gifts, the ringmaster in an unheralded Gloucestershire team that won six limited-overs trophies in three seasons.

On pitches the colour of gruel, Ian Harvey, Mike Smith et al created the anxiety, the asphyxiation, and as the veins popped in batters’ heads there was Jack the mosquito, puncturing their flesh for a slurp of claret. Barking – oh, he was barking – relentlessly at his teammates, he would habitually walk in front of the stumps to applaud and chivvy, all a pretext for irritating the batsman, getting in his space. It brought new meaning to occupation of the crease – here, in the sense of an invading army. The pickpocket had become a mobster. A bailiff.

I admired his brazen, cartoonish villainy. Face inscrutable behind those sunglasses, that daft hat and his bristles, Jack would narrate the batsman’s anxieties for the benefit of his swarming team. He gave this reluctant and increasingly part-time wicketkeeper something to aspire toward. Sure, my Teflon glovework would always be found wanting, but I could always usefully piss the batsman off.

It was not genteel comportment, but then the cricket I played wasn’t genteel. The existential stakes were high: glory, ignominy and self-esteem, all were forged by this innings, that shot, a catch, a victory. There was no place to be genteel. My nickname then was Dog (as in Scotty…), and the cricket was dog-eat-dog. And in that there was no better example, no more terrorising terrier, than Jack Russell, top dog of the underdogs.

Sunday, 9 November 2014

PETER SIDDLE DIARY

At the beginning of the summer I was contacted by an editor from ESPNcricinfo who told me they were going to launch a high-quality digital magazine, The Cricket Monthly, complete with typeface of the old Cricketer magazine.

He said he'd like to commission me to write a piece, and asked whether I had any suggestions. To be honest, I wasn't sure how straight to play this: after all, my four pieces (including one pending) for The Nightwatchman have covered what Jacques Derrida teaches us about Graham Onions' career-best 9-67, the great Aussie cordon (Healy, Taylor, Waugh, Warne, Waugh), having my foreskin trapped in my box by Dean Headley, and the comparisons between cricket and bullfighting.

I had a few other equally niche ideas, but in the end thought I'd go for something more accessible and mentioned that Notts had signed Peter Siddle for what they at the time thought would be a full season, an increasingly rare thing to get someone of almost top-rank stature for the duration of the summer. I suggested a diary. They liked it.

Notts were pretty good about getting me access to Pete, whom I spoke to on three occasions (I really ought to have tipped up more often at Trent Bridge, but the habitual dogsitting duties kept me out of Nottingham for the first 5 weeks of the season), and it was interesting to track his fortunes over the three months he ended up staying. The editing process wasn't quite so enjoyable, however, with every word agonised over and at least ten versions of the piece sent back to me.

The main problem, it seemed to me, was the lack of clarity over the brief. I suggested some writerly flourishes, some colour, and that sort of tone was OK-ed. However, when it came to editing my submission, many of these flourishes were tweezered out, to my mind devoiding the piece of much of its personality. I had occasion to wonder whether a more established writer would have had to endure the same treatment. I doubted it (the unconscious inclination to intervene would have tempered by the reputation of the writer; idiosyncrasies would be indulged). Then again, without a frame of reference regarding what they were after (TCM hadn't been published when I started), it was difficult to get a proper feel of what they were after, other than through the aforementioned brief.

Anyway, shits and giggles. It was my most lucrative fixed-fee commission to date. And, after more than a few emails with other sports writers sharing our gripes and grouches, I'm growing ever less concerned by the final piece that the public sees.

Vicious in the Shires

Saturday, 1 November 2014

CHELTENHAM LITERATURE FESTIVAL

Last month I was invited to the Cheltenham Literature Festival by The Nightwatchman, for whom I'd written three fairly eclectic pieces

— the first about what Graham Onions' career-best 9 for 57 could teach us about the 'deconstructionist' philosophy of Jacques Derrida (or vice versa); the next about the great Aussie cordon of Healy, Taylor, Waugh M, Warne and, in the gully, Waugh S; the latest about having my penis trapped in my box by Dean Headley

— with a couple more in the offing: about cricket's 'connection' with bullfighting and the Minor Counties' matches in the old Benson and Hedges Cup.

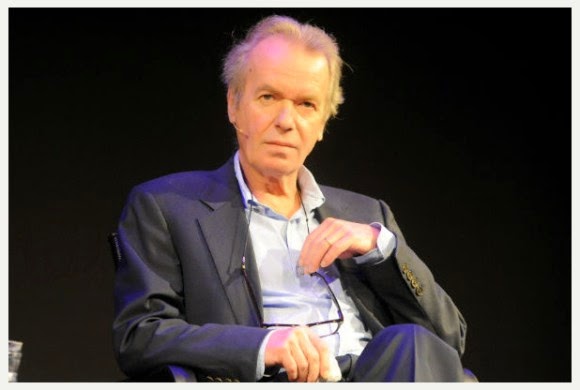

I was just as thrilled to meet Jon Hotten, aka 'The Old Batsman' [click here for an example of the man's talents], as I was about the prospect of bumping into various literary heroes: Salman Rushdie, Martin Amis, Kevin Pietersen...

Jon was chairing proceedings in the Waitrose / Nightwatchman tent, diligently mentioning the sponsor's name at the start of each session, expertly deflecting the intrusive interjections of one or two northern folk in dutiful attendance who seemed particularly keen to steal the, ahem, limelight from whoever it was talking. Apparently, there is no subject sufficiently esoteric for it not to be brought back to a tale about the Yorkshire League. The only thing that really kept 'Steve' quiet were the plentiful jam tarts and gourmet nuts on offer from Waitrose.

Anyway, I was there for a little over 24 hours, only attended one session that wasn't in our stall, but had a grand old time drinking and chewing the fat. I wrote a short piece about it all over on my (much neglected) non-cricket blog, Motionless Voyage, which I reproduce here because I'm essentially a very lazy person.

AMIS IS AS GOOD AS A MILE

It was an interesting experience at the Cheltenham Literature Festival, where the highlight of my talk — I was chucked a bit of a hospital pass by the organisers: “Cricket, the perfect sport for a spot of philosophy” — was being interrupted by a bumptious Yorkshireman (is there any other sort?), who, shortly after I’d told the not especially philosophical tale of getting my foreskin trapped in my box by Dean Headley when I was 16 years old, barked: “What’s your best cricket story? You tell me yours and I’ll tell you mine…”

On the upside, I went to (my writing hero) Martin Amis’s Q&A in the main tent, The Times Forum. He was talking about his new Auschwitz novel, The Zone of Interest, telling several hundred guests that “the black hole in Hitler Studies was his sexuality” and speculating that he was “probably a pervert rather than asexual. Maybe a coprophile”. I was due to ask the next question from the floor when the session was ended — good job, probably, as my heart felt like I was just coming up on a steroid overdose.

An hour later, having told my colleagues from the Waitrose / Nightwatchman stand what my question would have been while guzzling the complementary wine a bit too unselfconsciously, Amis walked into the writers’ hospitality lounge (out of my line of sight) and was momentarily stood alone. “Go and ask Martin Amis your question, Scott” said the editor, Matt. After a moment’s thought (about the same length of time I used to take at school when persuaded, or goaded, into doing the sort of idiotic though entertaining stunts that regularly got me put on daily report), I said, “alright then”.

“Hi Martin. So, I was going to ask you the next question when your session was wound up earlier.”

“Fire away”.

“Yeah, I was fascinated by what you were saying about the War being lost from 1941 and Hitler essentially spending the rest of it punishing the German people for their shortcomings. I once heard a definition of fascism as ‘a manic attack by the body politic against itself, in the name of its own salvation’. Does that chime with your knowledge of Nazi Germany? And, if so, was the average German complicit in that self-destructive delirium?”

He took a couple of steps away from me and put down his glass of wine. My ‘crew’ thought he was abandoning the conversation — and you couldn’t really have blamed him — but he then pivoted back and, after a beat, said: “Well, that definition might take some time for me to absorb, but there was definitely a lustful frisson [immaculately pronounced] in their administration of petty cruelties. They knew what they were up to, alright”. Then someone much more important and much less earnest than me caught his attention, and he was off air-kissing some Camilla or Priscilla in a Chanel suit.

I returned to the table, and received a small and un-ironic round of applause. “Did you take a photo of that, Matt?” “I didn’t, mate. I was too much in awe”. “No worries”, I said, secretly crestfallen. “But I’ve got to say, your body language was strong: hands in pockets, relaxed shoulders…”

Then Dame Judy Dench walked in. Heads turned. I had nothing for her, so went and got some more wine.

I was just as thrilled to meet Jon Hotten, aka 'The Old Batsman' [click here for an example of the man's talents], as I was about the prospect of bumping into various literary heroes: Salman Rushdie, Martin Amis, Kevin Pietersen...

Jon was chairing proceedings in the Waitrose / Nightwatchman tent, diligently mentioning the sponsor's name at the start of each session, expertly deflecting the intrusive interjections of one or two northern folk in dutiful attendance who seemed particularly keen to steal the, ahem, limelight from whoever it was talking. Apparently, there is no subject sufficiently esoteric for it not to be brought back to a tale about the Yorkshire League. The only thing that really kept 'Steve' quiet were the plentiful jam tarts and gourmet nuts on offer from Waitrose.

Anyway, I was there for a little over 24 hours, only attended one session that wasn't in our stall, but had a grand old time drinking and chewing the fat. I wrote a short piece about it all over on my (much neglected) non-cricket blog, Motionless Voyage, which I reproduce here because I'm essentially a very lazy person.

AMIS IS AS GOOD AS A MILE

It was an interesting experience at the Cheltenham Literature Festival, where the highlight of my talk — I was chucked a bit of a hospital pass by the organisers: “Cricket, the perfect sport for a spot of philosophy” — was being interrupted by a bumptious Yorkshireman (is there any other sort?), who, shortly after I’d told the not especially philosophical tale of getting my foreskin trapped in my box by Dean Headley when I was 16 years old, barked: “What’s your best cricket story? You tell me yours and I’ll tell you mine…”

On the upside, I went to (my writing hero) Martin Amis’s Q&A in the main tent, The Times Forum. He was talking about his new Auschwitz novel, The Zone of Interest, telling several hundred guests that “the black hole in Hitler Studies was his sexuality” and speculating that he was “probably a pervert rather than asexual. Maybe a coprophile”. I was due to ask the next question from the floor when the session was ended — good job, probably, as my heart felt like I was just coming up on a steroid overdose.

An hour later, having told my colleagues from the Waitrose / Nightwatchman stand what my question would have been while guzzling the complementary wine a bit too unselfconsciously, Amis walked into the writers’ hospitality lounge (out of my line of sight) and was momentarily stood alone. “Go and ask Martin Amis your question, Scott” said the editor, Matt. After a moment’s thought (about the same length of time I used to take at school when persuaded, or goaded, into doing the sort of idiotic though entertaining stunts that regularly got me put on daily report), I said, “alright then”.

“Hi Martin. So, I was going to ask you the next question when your session was wound up earlier.”

“Fire away”.

“Yeah, I was fascinated by what you were saying about the War being lost from 1941 and Hitler essentially spending the rest of it punishing the German people for their shortcomings. I once heard a definition of fascism as ‘a manic attack by the body politic against itself, in the name of its own salvation’. Does that chime with your knowledge of Nazi Germany? And, if so, was the average German complicit in that self-destructive delirium?”

He took a couple of steps away from me and put down his glass of wine. My ‘crew’ thought he was abandoning the conversation — and you couldn’t really have blamed him — but he then pivoted back and, after a beat, said: “Well, that definition might take some time for me to absorb, but there was definitely a lustful frisson [immaculately pronounced] in their administration of petty cruelties. They knew what they were up to, alright”. Then someone much more important and much less earnest than me caught his attention, and he was off air-kissing some Camilla or Priscilla in a Chanel suit.

I returned to the table, and received a small and un-ironic round of applause. “Did you take a photo of that, Matt?” “I didn’t, mate. I was too much in awe”. “No worries”, I said, secretly crestfallen. “But I’ve got to say, your body language was strong: hands in pockets, relaxed shoulders…”

Then Dame Judy Dench walked in. Heads turned. I had nothing for her, so went and got some more wine.

Thursday, 30 October 2014

THE OLD WICKETKEEPER

One of my favourite cricket writers is Jon Hotten, perhaps better known as The Old Batsman. I was fortunate enough to meet Jon at The Cheltenham Literature Festival a few weeks back, where he chaired the talk I was asked to give on cricket as the perfect sport for a spot of philosophy. Needless to say, we sized up the audience (such as it was) and decided that a better avenue was telling a few yarns, all the while shoehorning in the odd vaguely philosophical reminder here and there.

Both John and I contributed to the October edition of The Cricket Monthly, ESPNcricinfo's new digital magazine. My piece was a (painstakingly edited) diary of Peter Siddle's season with Nottinghamshire, while Jon pondered the ever-changing role of the wicketkeeper.

I have chosen two extracts from the latter that illustrate Jon's masterly writing, its economy, elegance and snap. The first spins a wry yarn about an old wicketkeeper with whom he shared a dressing room, the second shows off his characteristic acuity at spotting emerging trends in the game, charting its evolutionary direction.

* * *

The concept of the club kitbag has almost died out now, in an age where gear is marketed, coveted and fetishised, but back then most sides had a couple of guys who weren't bothered about owning equipment of their own and who were happy to delve around in the club bag for a pair of mismatched pads, some sweat-stained gloves, maybe a mildewed thigh pad they could use and chuck back at the end of the day.

Within this particular club bag it lay, cold and ancient. A stitched-in manufacturer's label described it as an "abdominal guard" but that hardly did it justice. It looked like something Henry V wore to Agincourt, a great tin codpiece attached to a wide, padded V-shaped belt that had to be stepped into like a jockstrap and then secured around the waist with a couple of long ties.

It was universally known as "Cyril's Box" after the only man who would (or could) wear it, the 1st team wicketkeeper, Cyril. He was a remarkable man, mid-fifties, squat, powerful, with giant, hooked hands permanently ingrained with grease. I never discovered what it was that Cyril did for a living, but it was some kind of hard physical labour that had produced both great strength and admirable stoicism. He rarely said anything. Instead he turned up in the dressing room every Saturday, stripped off his street clothes, retrieved the box from wherever he had thrown it the week before, strapped himself in, pulled the rest of his gear over it and walked out onto the pitch.

Like the young Rod Marsh, Cyril had iron gloves. The ball often used to fly off them at tremendous speed, accompanied on crucial occasions by a muttered oath. He'd sometimes stand up to the opening bowlers, usually without explanation, and it was then that the abdominal guard earned its corn. The ball would smack Cyril in the vital area and then ricochet away with a metallic clang. On one occasion a batsman was caught at second slip direct from Cyril's box and the game took a while to restart: several people were actually crying with laughter; Cyril wasn't one of them.

After a match Cyril would silently remove his box, sometimes pushing out a dent with a thick thumb. He'd get changed back into his street clothes and then wander up to the pub, his love for the game expressed perfectly and eloquently in the slow satisfaction of his walk.

* * *

It would be easy to see this [keepers picked on batting ability] as the future of wicketkeeping forever, and yet cricket is never still. I would suggest that it's in T20s, where the keeper's role looks the most disposable, that the change may come.

The thought began to form as Hampshire, my county, had a glorious little run with the white ball, one that brought them two domestic one-day cups and two T20 titles. These rewards seemed at odds with the ability of the team, who were financially outgunned by far richer counties and lacked a box-office overseas performer. What they had, though, was a very particular method, especially at their home, the Rose Bowl, where wickets were low and skiddy. They used lots of medium pace and flat spin and choked the life out of big-hitting teams. As the tactic developed, their remarkable young wicketkeeper, Michael Bates, became central, often standing up to the stumps for most of the innings.

What Hampshire had hit on was simply an equation of resources. T20 is a game for specialisation, because unlike Tests and ODIs, those resources are rarely exhausted in the time allocated.

At the start of each game, the wicketkeeper is the only specialist position guaranteed to be able to affect a minimum 50% of the match while using his primary skill (the 20 overs for which they keep). A bowler has 10% (four of 40 overs), the two opening batsmen an unlikely maximum of 50%, the other batsmen a sliding downward scale from there.

The wicketkeeping position can therefore be reimagined as an attacking option. It's an opportunity to reduce the effectiveness of the batsman by keeping him in his crease against seam bowling, thus reducing his scoring options. While it's hard to quantify exactly how many runs might be saved by a gloveman capable of standing up to the seamers, it is a move that would challenge many of the techniques of T20 batting. It might not be fanciful to guess that the score might be limited by 20 to 30 runs per innings, at least until batsmen adjust in turn.

It was easy to go into some kind of reverie when watching Bates; he brought back memories of Taylor standing up to Botham, of the impish skills of Knott, the silken hands of Russell.

These men were a different shape to the gym-produced, identikit bodies that burst forth from the tight-shirted present. The demands of the job mitigate against the physique needed for power-hitting, and a specialist wicketkeeper might have to be regarded a little like a bowler, with his main contribution coming in the field. But without running the stats, it would be interesting to know how often the seventh batsman has done the job when six others couldn't.

At the time of Hampshire's successes there was much talk of Sarah Taylor, England Women's sublimely talented wicketkeeper, playing a match for Sussex 2nds. While mixed sides may be counterproductive to both the men's and women's games in the long run, a talent like Taylor's would fit well into a T20 game, where her batting would be less relevant.

Hampshire dropped Bates when they signed Adam Wheater, who is a better batsman. Many, including me, were sad to see it happen, because watching Bates was a reminder of what an electrifying skill wicketkeeping can be.

Wonderful writing.

Thursday, 17 July 2014

BULLFIGHTING AND THE LEAVE-ALONE

A short essay for ESPNcricinfo comparing the batsman's leave-alone with the bullfighter's pass. There is a longer version – comparing the structure of the bullfight with a day's play – due in The Nightwatchman next April, since that is the time when the thrilling leave, the dangerous projectile that is the ball brushing past the flanks of the batsman...

Corrida of Uncertainty

Thursday, 26 December 2013

IMMY AGAIN...

I have already

told the story of Imran Tahir’s exploits for Moddershall in 2008 a

couple of times, but I had never before been paid for it. So it was nice to

have someone – in this case, Wisden

India – accept the pitch and take the story to a few more people, who might

thereby have their occasionally dismissive attitude toward him tempered.

For that reason, it was extremely gratifying that The Guardian picked up on the piece and

made it one of their Favourite

Things This Week, although I wasn’t alone in thinking describing its author

as “venerable” might be a bit of a stretch. Or me writing with “warmth” and “charm”…

THE NIGHTWATCHMAN, ISSUE 4

At the start of this month, Issue 4 of Wisden’s cricket

quarterly, The Nightwatchman,

hit the stands. Explicitly modeled on the football journal, The Blizzard, the cricketing stablemate

provides a platform for longform journalism and for writers to pursue niche

interests that the world of SEO and quote-harvesting would ordinarily preclude

from being published.

In my case, that means a long piece exploring what Graham

Onions’ career-best spell of 9 for 67 against Nottinghamshire at Trent Bridge

Anyway, having previously written a couple of pieces for the

latter, I’m extremely honoured to have become only the fourth person – after Blizzard editor Jonathan Wilson, Wisden India editor Dileep

Premachandran, and the enormously talented and knowledgable Rob Smyth – to have

completed the Nightwatchman–Blizzard

double. Now, if only I could monetize this niche, French Theory meets sports

commentary, then I’d be a happy bunny.

Sunday, 21 April 2013

WISDEN, BABY!

Well, well, well. It’s fair to say I was highly surprised

and very happy to learn that I’d made an appearance in this year’s Wisden, the

150th edition of the famous old almanack, now under the stewardship of Lawrence

Booth, its youngest ever editor. Apparently, I’m mentioned in an article about blogs and bloggers (p185) and how they’ve changed the cricket-writing landscape, penned by the excellent legsidefilth

(whose real name will be revealed when I buy the old yellow brick). He wrote: “Scott

Oliver at reversesweeper takes a more academic and philosophical approach,

combining tales of league cricket with and against [---], with references to

David Hume and non-linear thermodynamics. As you do”. Touched.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

%2B001.jpg)